Breaking Wind: How Wrigley’s New Video Board Will (or Won’t) Impact Home Runs

Despite a nice collection of power hitters, the Cubs have hit nary a home run at Wrigley this year. While that’s not too surprising given the cool, heavy air in Chicago this time of year, many had speculated that the team’s new monolithic testament to modern technology would help baseballs to leave the yard.

This theory was advanced by Jorge Soler hitting it during batting practice the other day, though the weather was a bit more amenable at the time and, well, that situation is custom-made for moonshots.

It stands to reason that the video board in left would serves as a very expensive wind screen, creating a wormhole in the ballpark’s atmosphere that would allow balls that would have otherwise died at the track to travel to the bleachers and beyond. Take that, Stephen Hawking!

I had been pondering a project involving some research on the potential impact of the new board, but could never really settle on a jumping-off point. But then I saw that my work had already been done for me by Scott Lindholm of BP Wrigleyville* (yes, Baseball Prospectus has a Cubs-centric outlet headed up by the incomparable Sahadev Sharma).

Never one to build an observation tower with my own clumsy hands when I can get the same view by standing on the shoulders of giants, I wanted to excerpt some of Lindholm’s article, A Jumbo Wind Screen? Maybe Not, here for your consideration.

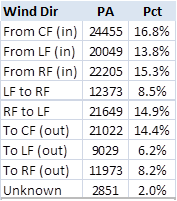

The video board is in left field, and as such would block any winds from the north. Baseball-Reference has game time weather data going back to 1991, including wind speed and direction, and this is how the wind patterns break down:

To explain, there have been over 24,000 plate appearances in which the wind was blowing in from center field at the beginning of the game, or almost 17 percent of the time. In general, winds were blowing in around 45 percent of the time, crosswinds around 24 percent of the time, and blowing out around 28 percent of the time.

This doesn’t even take the kind of hit into consideration. The typical single is a ground ball, doubles and triples are often line drives hit to the gaps, and rarely do batted balls of these types rise to the height where the wind would have an appreciable effect on their trajectory.

Which leaves home runs. The ESPN Home Run Tracker shows there have been 1,504 home runs hit in Wrigley Field since 2006, with the Cubs hitting 737 of them and their opponents 767.

For there to be an effect, the ball must be hit high enough for the video board to block winds that would have kept it in the park. I’ll make an educated guess that the left field wall is 30 feet high, and by wall I mean the outside wall, not the left field fence—the outside wall provides a wind block of its own. So, the video board might have an effect on balls hit to left field with a maximum elevation between 30 and 75 feet—lower and it doesn’t matter, and higher, the ball is above the video board’s height.

Since 2006, of the 463 home runs to left, 157 (the ones hit at an elevation between 30 and 74 feet, or around 11 percent of all home runs) might have received some boost from a video board that blocked the wind—and 89 percent wouldn’t. I could add another layer of data with home run distance, but at this point it’s an exercise in numerical masochism.

Lindholm’s full discourse contains several more charts and a great deal of additional information, so I highly recommend taking a look if you haven’t already. But long story short, the impact of the video board on wind patterns and home runs at Wrigley is generally negligible.

Then again, that 11% Lindholm references would apply largely to right-handed power hitters, guys who are going to be pulling a majority of their home runs to left. In Soler, Kris Bryant, and (fingers crossed) Javier Baez, the Cubs have a young core of hitters who might be able to leverage that small advantage more than most teams.

Again, this stuff is highly speculative and, as such, can’t be projected with any reasonable sense of accuracy. But that doesn’t mean it’s not fun to talk about. And love it or hate it, I think we all agree that we’re going to cheer each time a Cubs player hits the video board with a home run.

*They’ve not asked me for any input yet, but with the idea that you should “expect to see the same quality writing you get at [BP’s] main site,” I’m not exactly holding my breath.