Heyward and Rizzo Battling BABIP Issues, Primed to Break Out

How’s the old saying go: Ain’t that a BABIP? No, that’s not it. Life’s a BABIP, then you die? Son of a BABIP? No, that doesn’t sound exactly right, but I do know that I’ve used something along those lines to curse the misfortunes of a couple Cubs players in particular this season.

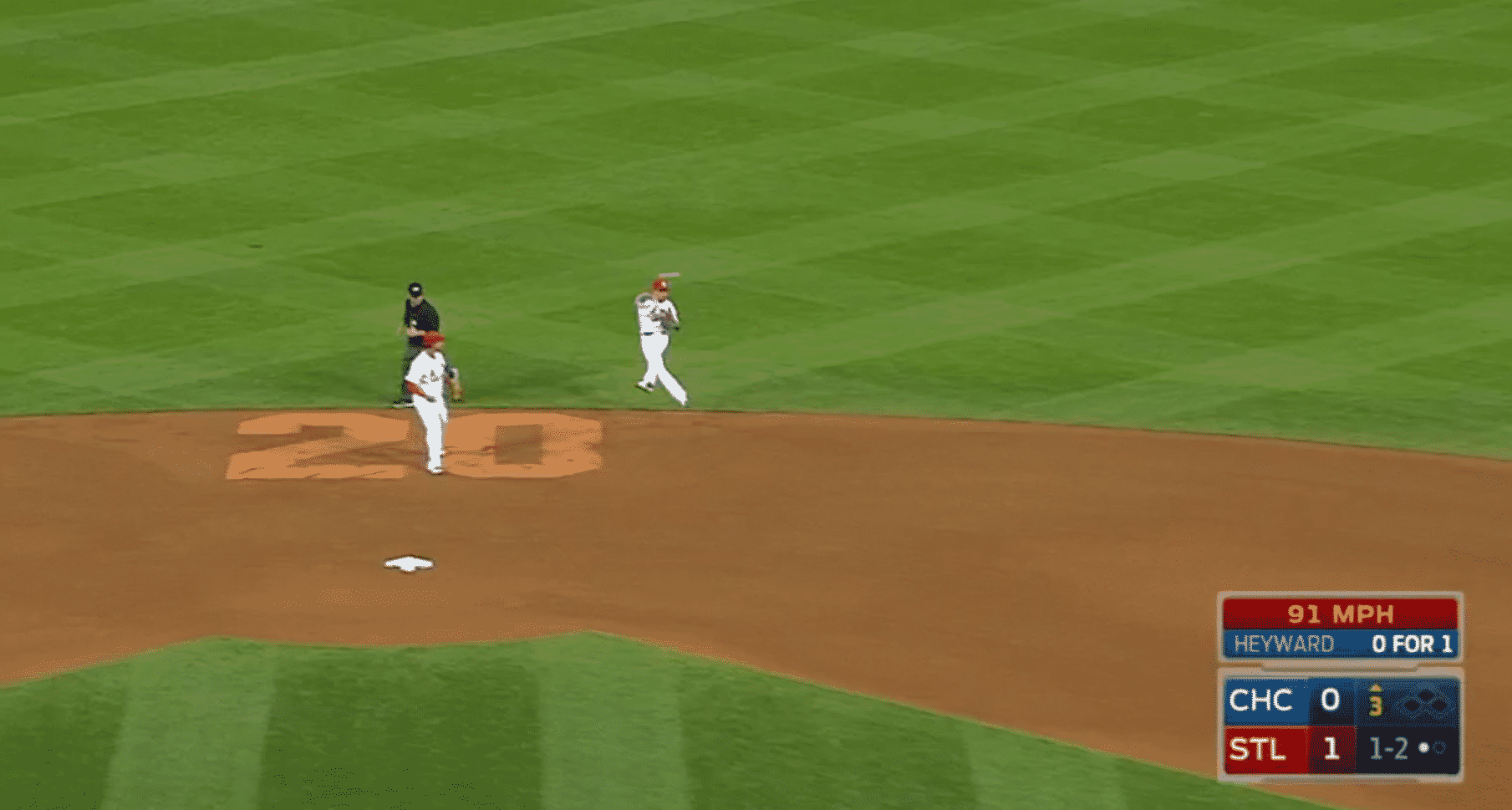

In his first at-bat of Tuesday night’s 2-1 win over the Cardinals, Jason Heyward laced a ball right back up the middle at 92 mph. It was the type of hit you’d expect to end up in center for a clean single, but shortstop Ruben Tejada got enough of it to knock it down and make the toss to Kolten Wong to force Dexter Fowler at second base. As if to further illustrate the ever-shifting whims of the BABIP (that’s batting average on balls in play for the uninitiated) gods, Kris Bryant chunked a swinging bunt that left the bat at roughly the speed of an eephus pitch (54 mph) and nestled safely in the grass along the third base line without a play.

The BABIP giveth and the BABIP taketh away.

At the risk of losing some of you who believe that I’m worshiping at the feet of false idols, I want to explain a little something about BABIP (if you have a firm grasp of this concept and its application, please proceed a couple grafs down). I’ve see this metric conflated with batting average in some cases or decried as a newfangled interloper meant to supplant the most vaunted of hitting stats.

But while batting average is a measure of how often a batter hits safely in his total number of at-bats, BABIP eliminates strikeouts, home runs, and sac bunts to look only at what happens when a hitter actually puts a ball into the field of play with the intent of getting a hit. It is not a measurement of pure skill — though players who hit more line drive drives and make more solid contact should experience higher BABIP numbers — but seeks to illustrate how lucky or unlucky a given player has been.

The league average fluctuates from year to year, but a BABIP of .300 is more or less the accepted definition of normal for an MLB hitter. There are obvious exceptions on both sides of that mark, but we can generally assume that a player who skews heavily to one end or the other is experiencing either good or bad luck. If you’d like more on the topic, I wrote a few months back about Kris Bryant’s exceptionally high BABIP in 2015 and what it means for him going forward.

But let’s get back to Heyward, whose first trip to the plate wasn’t the only time he came just a couple inches from a base hit. In the 3rd inning, he slapped a sharp grounder to the right side of second that Wong was just able to reach to make a great backhanded play. In the 7th, Heyward lined out hard to Matt Holliday, who didn’t really have to move. In the 9th, he once again forced Wong to range to his right for the out.

J-Hey was 0-for-5 in all (he struck out looking when Jaime Garcia absolutely grooved a slider; I posited at the time that Heyward was taking all the way after seeing Yadier Molina setting up outside and was frozen despite the mistake pitch) and 0-for-4 on balls in play, dropping his slash line to .170/.267/.207 and his BABIP to .225. As anemic as that appears, however, it’s still 86 points higher than the man playing in front of him.

That’s right, Anthony Rizzo is currently sporting a sickly-looking BABIP of .139 and a slash line of .163/.339/.388. Before I continue, I’d like to take a moment to marvel at that OBP. On the whole, Major League hitters reach base at about a .315-.320 clip, and that’s with batting averages sitting in the low .250’s. So the average hitter should have an OBP maybe 65-75 points higher than his batting average, with 100+ points signifying a really good on-base guy.

Rizzo’s OBP is 176 points higher than his average, people. That’s not normal. Also not normal is that insanely low BABIP, which is less than half of his career average of .282. Normally an incredibly consistent performer in terms of monthly splits, it’s very reasonable to believe we’ll see Rizzo become the beneficiary of some good fortune very soon and very often. More on that in a bit.

His fellow lefty is a bit of a slow starter, but appears similarly primed to bust his current slump.

Heyward carries a career March/April BABIP of .252, but he has never posted a full-season number lower than .260 and his overall career mark is .308. A quick look at his BABIP numbers by month (May – .290; June – .324; July – .320; August – .346; Sept/Oct – .311) show a very high likelihood for positive regression. Just yesterday, I wrote that he doesn’t have to hit to have an impact, but I think we’re going to see in short order that he’s quite capable of helping the Cubs offensively as well.

When you consider that the Cubs’ next 11 games following Wednesday’s finale in St. Louis will take the Cubs to Cincy for four games and then home for three each against the Brewers and Braves, you can see how Heyward and Rizzo might be able to get off the schneid. Not only do the park factors* play favorably for BABIP in general, but Great American Ball Park in particular is a haven for lefties, especially those with a little pop (Home run/fly ball factor of 115.5 is tied with Coors Field for tops in baseball). A little home cookin’ should do the Cubs well too.

More than a handful of fans have expressed worry over the low batting averages of these two players, among others, but any fears should be allayed by the time we turn the page to May. Their stats right now are unsustainably low, which means they can only improve from here. And if all this statistical logic doesn’t help to calm your nerves, just remember: the Cubs are 11-3 with two of their best everyday players batting 30 or more points below the Mendoza Line.

And when that all evens out…hoo, boy.

*In terms of park factors, 100 represents neutrality. Anything below means that a park impacts a given stat negatively, while anything above is positive. Therefore, a park factor of 115.5 on HR/FB means that GABP experiences 15.5% more home runs per fly ball hit than the average park. That’s perhaps a bit of an oversimplification, but you get what I’m saying. Well, I think you do.