Cubs Among Biggest Losers in MLB’s Revenue Projections, Impact on Players Still Murky

I know many of you are tired of hearing about it by now and I’ve nearly reached the point at which I’m tired of writing about it, but the battle between the league and players over revenue isn’t going to end anytime soon. As simple as it seems to just accept a 50/50 split of the money generated by whatever form of season they’re able to stage in 2020, such a deal could have serious adverse impact on the players. Factor in the distrust the union already has for owners and you’ve got a very complicated situation.

Ed note: I’ll do my best to lay this all out as simply as a I can, largely because I’m a pretty simple man, but some of the information here may require a little context. Much of that can be found in previous pieces here and I’ll include plenty of links to those as I see fit. You can also see some of Brett Taylor’s work at Bleacher Nation; he’s a much bigger nerd than me and can thus provide a different perspective for those of you who are likewise nerdy.

Think about it this way: I offer to bring you in as a partner on Cubs Insider and I tell you we’re going to split the money right down the middle. Thing is, I’m the only one who has access to those figures and I tell you to trust me to pay you out your fair share. Not only are revenues severely depressed right now in the first place, but you’d probably have reason to wonder what I’m including in my calculations since you can’t see them.

That’s why the union has requested “a slew of financial documents that detail the industry’s finances” per a recent AP report. That came in response to the 12-page presentation from the commissioner’s office to the union titled “Economics of Playing Without Fans in Attendance” distributed on May 12 and subsequently obtained by the AP. In it, the league explained that losses from player salaries would average $640,000 per game over an 82-game season with no fans.

Based on the calculations put forth in the document, a roughly $4 billion total loss by the league would result in players getting 89% of revenue if they maintain their prorated salaries. That figure is based on aggregate per-game salaries of $1.67 million compared to average per-game revenue of $1.87 million. Extrapolated out over the season, that’s $2.36 billion in salaries out of a total revenue of $2.87 billion (82.2%, still much higher than players’ typical cut).

Setting salary percentages aside for a moment, I think we can all understand that MLB as a whole figures to lose quite a bit no matter how the season plays out. The initial revenue projection prior to COVID-19 shutting things down sat at $9.967 billion, so that’s now reduced to less than a third of what was expected in spite of hoping to play half the season. If, that is, you believe the owners’ numbers.

According to the AP report, “MLB said 2019 revenue was 39% local gate and other in-park sources, followed by 25% central revenue, 22% local media, 11% sponsorship and 4% other.” Those numbers can vary greatly from team to team, another complicating factor in this whole mess. Speaking to a group of season ticket holders in a video chat about the 2020 season, Tom Ricketts said the Cubs derive 70% of their total revenue from gameday activity.

That claim seems very dubious absent the numbers to back it up, though factoring in ownership’s Hickory Street Capital holdings around the ballpark makes it more plausible. It was initially maintained that HSC was a wholly separate entity, but the Cubs have admitted more recently that there’s mutual benefit and that revenue generated by non-Cubs business can benefit team payroll. Between those ventures and what would otherwise have been high attendance figures, it makes sense that the Cubs are near the top of the list when it comes to projected losses.

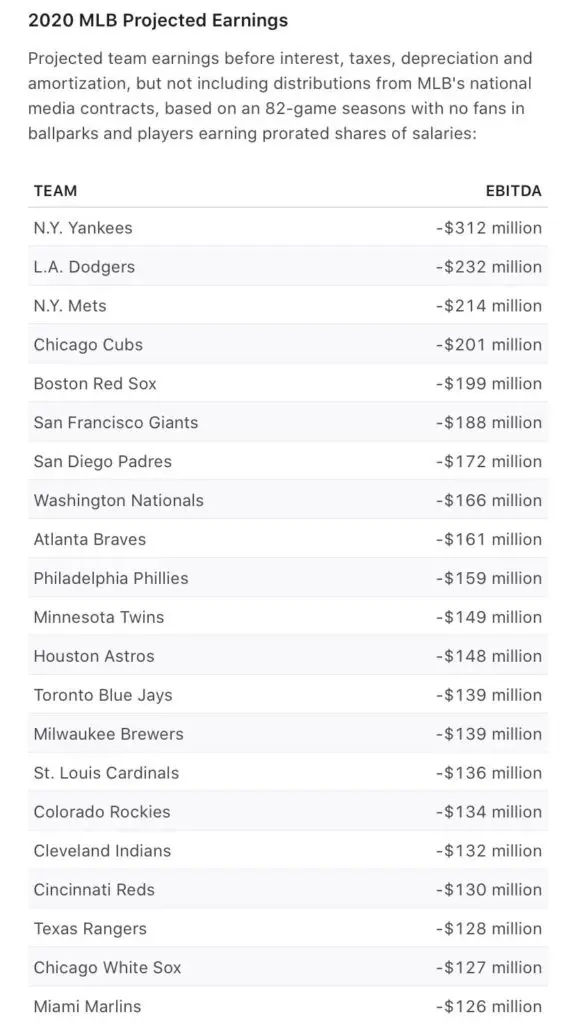

Per the report, the Cubs could be at -$201 million EBITDA — an accounting term used to measure profitability and comes from earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization — for the 2020 season. That’s just behind the teams in LA and New York and just ahead of Boston.

To be sure, there’s a lot of wiggle room in all of these figures and we’re only dealing with projections that are based on what we know as of right now. There are myriad issues with debt and credit, some of which the league reports will force several teams out of compliance with the CBA’s rules on proper debt-to-asset ratio. Then there are the unknowns about whether and how expanded playoffs would alter the league’s take from broadcast partners.

The postseason alone reportedly brings in $787 million in media money, which the document details clearly: $370 million by Fox, $310 million by Turner, $27 million by ESPN, $30 million by MLB Network, and $50 million from international and other. It’s conceivable that those numbers could grow should the league make it to a postseason that features 14 teams and has less competition for viewership than usual. Then again, there’ll be a lot to make up for.

The league projects a $980,000 revenue loss from regional sports networks from each game not played, bringing the total take from $2.3 billion to $1.2 billion in an 82-game season. Again, that can vary by team and broadcast partner, with the Cubs potentially taking more of a bath than initially feared since they are a full partner with Sinclair Broadcast Group on Marquee Sports Network.

There’s a lot more in the projections regarding stadium depreciation, non-cash add backs, principle payments, etc, but MLB says “EBITDA has been within $250 million of break-even annually since 2010.” The idea here is that the league wants the players to understand what a fine financial line is being walked and how demanding they be paid in accordance with their contracts could upset the apple cart. Except that it’s the players that drive those revenues in the first place.

A little cocktail napkin math tells us that, under normal circumstances, the players would make up about 52-55% of MLB’s total expenses. That’s considering salaries for MLB and MiLB players, pension, benefits, and draft bonuses. Even at the lowest end of that figure, a 50/50 split represents a $200 million slice of pie that would stay with the owners over the course of a full season. It’s still $100 million in their favor in the shortened season.

Now consider that the projected cost to sign amateur players has dropped from $537 million to $440 million as a result of the truncated draft. That’s $137 million the owners have already pocketed, so we’re looking at perhaps more than a quarter-billion in “savings” at the direct expense of the players. Again, this is all using projections and percentages based on what would have happened in comparison to a full season of revenue.

As it currently stands, the league’s proposal calls for players to receive half of the projected $2.87 billion in revenue, which comes to roughly $1.435 billion. That’s about $925 million less that they’d receive under the terms of prorated salaries agreed to back on March 26, though, again, this is all subject to change based on reality and the fact that my math could be off.

What this all comes down to here is that everyone involved is going to make less money in 2020 no matter how it shakes down, but the owners are really the ones holding more of the power and information here. The players, understandably so, don’t trust those in power to present them with accurate figures that would feed the pot that will eventually be split. Therein lies the real issue, though it goes beyond just this season.

Giving ground in ongoing labor negotiations that will continue through 2021 means even more contentious talks as related to the next collective bargaining agreement for the 2022 season. Players want transparency and might be willing to give a little should they receive it. Owners understandably want to cut costs at every possible turn, since they’re not in the business of losing money. As things are currently laid out, however, those cuts appear to be disproportionately impacting the players.

I’ll warn for maybe the fifth time that these numbers are all based on projections, so they’re all subject to change. You’ve also got to factor in my inherent bias, which applies to both the understanding of the concepts involved here and my decidedly pro-player stance. At the end of the day, it’s just going to come to how willing the union is to accept both the risks of playing and the veracity of the league’s claims. I still believe the desire to play will eventually result in broader acceptance of those matters, though I hope owners are the ones making more concessions.

We’ll just have to wait and see at this point.