Let’s Set Record Straight on Launch Angle (Again) While Maybe Fixing MLB’s Contact Issues

You may as well start calling me Michael Corleone because I keep getting pulled back into the conversation about launch angle, specifically how it’s neither a new concept nor a dangerous siren song for hitters. The best way to find success at the plate at any level of baseball is to hit the ball hard and hit it in the air. It’s really that simple.

In order to accomplish that task, it’s imperative that a swing “launches” the ball into the air rather than on the ground. Anyone who says or teaches otherwise is dead wrong and should not be trusted. While there may be situations in which a bunt or slap hit makes sense, all legitimate data supports the idea that the best results are achieved in the air.

So why, then, is there still so much pushback and even outright anger when it comes to launch angle? The short answer is ignorance. Too many people have mistakenly conflated a simple measurement with an entire philosophy, thereby failing to acknowledge either statistical reality or a wealth of mutual teachings that otherwise line up pretty closely.

I got started down this rabbit trail after watching a video in which former Rockies great Dante Bichette was explaining hitting mechanics in the cage. As an aside, it’s really wild to look at Bichette’s career .299 average with 274 homers and then see that he only exceeded 1.8 fWAR once in a season (2.8 in 1993) and had a career wRC+ of just 104. That’s what happens when you play in Denver during the steroid era.

In any case, I was struck by how Bichette was illustrating the idea of “loft,” and not just because he certainly benefitted from it in his day. More than that, the concept he espoused just struck a sour note when I heard it because it didn’t match at all with what I’ve learned and taught.

“It ain’t all about exit speed, man, it’s about line drives and solid contact,” Bichette said. “It ain’t about loft. Everybody’s talking about loft. You know what loft is? I’ll tell you what loft is.

“Here’s what loft is [takes small steps back from tee]…Catching it out front. That’s all loft is, is catching the ball a little further out front.”

Dante talking – Loft, His approach & 2 strike hitting. Upon the hundreds of hours of these talks over the last 5+ years, this 2 mins and 30 seconds of simplicity, is probably the most difficult for a hitter to buy into. When to play out front and when not too! pic.twitter.com/MZkYKeXT1l

— Stance Doctor (@StanceDoctor) October 17, 2020

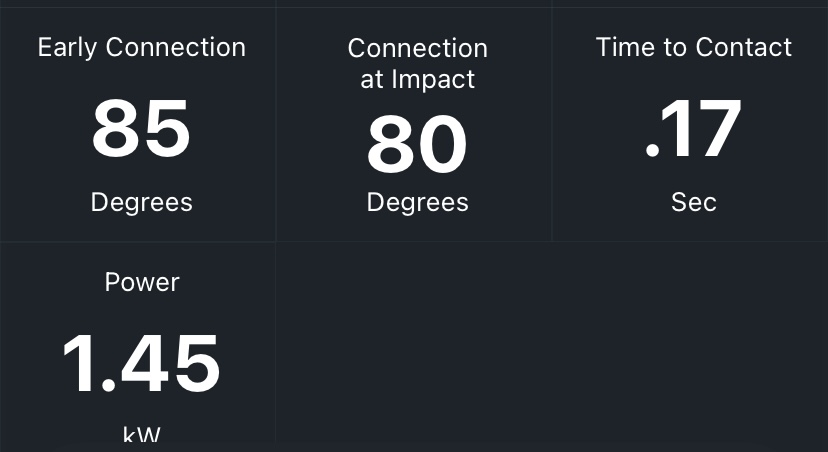

First of all, hitting the ball in the air isn’t just about catching it a little further out front. It starts with having proper early connection, which Blast Motion defines as “the relationship between the body’s tilt and the vertical bat angle at the start of the downswing.” That’s a fancy way of saying the angle between a hitter’s bat and torso, which would ideally average 90 degrees as their hands are coming forward.

There will be some variance, of course, but the idea is to be as close to the right position as possible with increasing frequency. That not only encourages a swing plane that meets a pitched ball for solid contact, but also allows the hitter to adjust because they’re more balanced. It’s important to get the bat on-plane and into the zone early to provide the best chance to drive the ball with authority.

The idea that hitters are creating loft simply by catching the ball out front really doesn’t make sense, though there is merit to what Bichette explained. It’s just not really for the reasons he lays out. For more on that, I turned to someone who’s previously dispelled a few myths about the so-called Launch Angle Revolution.

“As a hitting instructor, I want a hitter to say to me, ‘How deep should I let it get?’ Mike Bryant recently shared with CI. “Well, where’s that spot? It’s out in front of the front knee. It’s one or two balls maximum depth in front of the front knee. And if you look at a hitter hit from the side, they’re making contact one ball in front of the front foot when they’re really nailing it, because the swing is maximizing its bat speed.

“That’s at full extension when your arms form that ‘V.’ And then from that point, the swing starts to slow down. It’s speeding up prior to that. So if your arms haven’t fully extended yet, you’re still leaving some bat speed on the table.”

That alone seems like a good enough reason to make contact out in front of the plate, but there’s more to it. The timing involved in hitting at any level, especially in the big leagues, is so precise that every fraction of an instant matters. As such, a hitter can ill afford to cede leverage to his opponent.

“Here’s the thing, that sacred part of the plate for pitchers is the very front of the plate. That’s where the K-Zone is drawn, right at the very front of the plate. When you can enter the strike zone on a hitter, the minute the ball gets to the front of the plate, the pitcher gains a major advantage.

“So you don’t want to let the ball get deep. You don’t want to hit it over the plate. You want to hit it in front of the plate. Don’t let it travel, don’t let it get deep.”

This all seems to make sense so far, at least based on my own rudimentary understanding of hitting. And the thing is, it’s all common sense. None of this is even moderately revolutionary, it’s just that we’ve got the numbers to measure these results all the way down to the lowest levels of the sport. Using a Blast sensor will give numerous swing metrics that can be synced up to video for real-time analysis.

From there, it’s a matter of using the numbers to help guide a hitter’s feel for a repeatable swing that produces the best possible outcomes. That includes visualizing the contact point when doing tee work since that really enables the hitter to focus on the ball and establish habits.

“You put the ball on the tee and you don’t wanna hit the middle of the ball,” Bryant explained. “You wanna hit the bottom third of the ball because when you hit the bottom third of the ball and there’s movement on it, you’re actually hitting the middle of the ball because of the angle that’s been created.

“This is why you have to think launch angle, because you have to hit the bottom of the third part of the ball and view that part of the ball to actually get the middle.”

If you’re having trouble wrapping your brain around exactly what he’s saying here, just remember that a tee is stationary and the ball remains parallel to the ground at all times. A live pitch, however, is coming down at an angle that will vary based on the size and release point of a given pitcher. So the swing needs to hit the bottom half of a stationary ball in order to hit the center of a pitched ball.

“If you meet a pitch on a six-degree angle coming up to the ball and it has six-degree depth on it, it’s gonna go right back to where it came from,” Bryant said. “It’s gonna go right to the release point. If you hit the middle of the ball, it’s gonna be a line drive right back to the pitcher. It might get high enough to get over the shortstop, but doubtful.”

You can see the value of hitting the ball in the air by reviewing Statcast’s hit probability numbers for launch angle, which start to rise precipitously once you get above -5 degrees. Batting average peaks at 13 degrees and wOBA is highest at 27 degrees due to the increase in home run percentage. Very few homers are hit at anything less than 20 degrees, with a vast majority falling from 24-35 degrees.

Think launch angle isn't important? Here are expected BA/wOBA/HR% based on LA numbers in MLB in 2020:

-50: .165/.205/0

-10: .189/.189/0

0: .332/.337/0

10: .652/.636/0

20: .580/.695/6.4

30: .426/.739/30.3Really starts to fall off after 30, but the results are clear.

— Evan Altman (@DEvanAltman) December 23, 2020

The best hitters in the game realize this, which is why you see an increase in their average launch angles over the years. Mike Trout‘s has increased almost every year to a high-water mark of 23.1 degrees in 2020. Christian Yelich went from very good to great when his LA numbers increased in 2018 and ’19 following his trade to Milwaukee. Not surprisingly, he dropped to 7.1 degrees during the shortened season and saw his performance drop off despite a higher average exit velocity.

There’s plenty of skepticism about Robinson Cano given his PED suspension, but his numbers from a few years ago indicate something other than just pharmaceutical assistance. His average exit velocity in 2015 was at a career-high 91 mph, but his average launch angle of 5.4 degrees was a career-low as he had his worst season since 2009. The following season, his EV was at a career-low 90.2 mph but his LA was up to a career-best 11.5 degrees and he hit a career-high 39 homers in one of the best offensive seasons of his career.

We’re not talking about drastic changes or trying to swing steeply at everything, but it’s pretty clear that better results can be achieved by employing a swing meant to launch the ball. Okay, well if putting emphasis on hitting the ball in the air is such a good thing, why are there so many strikeouts and lower overall batting averages?

“If you want more balls in play, you’ve got to force the pitchers into the zone,” Bryant said. “What’s gonna force the pitchers into the zone more than anything? A strike is a strike and a ball is a ball, there’s no gray area. The ball’s either in the strike zone or it’s not. That’s an absolute.

“So if they want more contact, put an electronic strike zone in. Because hitters won’t have to swing at pitches outside the zone that they can’t hit anyway.”

The other very obvious factor here, both for hitters and umpires, is that pitchers today are throwing nastier stuff with higher velocity than ever before. I’m old enough to remember when seeing 95 mph was a big deal, but now that’s pedestrian. Along with specialized roles and workouts, increasing knowledge of baseball-specific physics like seam-shifted wake has produced waves of filthy pitches that only luck can defeat.

Now imagine trying to call discern whether and where some of those offerings actually entered the strike zone. Setting aside the disdain for some of the game’s worst practitioners, even the most ump-friendly among you have to agree that human error will soon reach unacceptable levels. For the record, I think we’re well past that point and it’s just a matter of ensuring the technology is airtight.

The league and union would also have to agree on the application and location of the zone, which is a three-dimensional space we too often view as a plane. There’s also the matter of placating pitchers, who could be hurt by this at least as much as hitters benefit. Forcing them to work within a zone that is no longer malleable could mean worse numbers and lower contracts across the industry.

Between that and a presumed increase in the pace of play, you’d think the league would be all over the implementation of an electronic zone. But I digress.

As you can see, this topic is far broader than what too often becomes a focused discussion about a single metric. Anyone out there railing against the benefits of hitting the ball in the air is being foolish and any coach trying to isolate a pronounced uppercut swing as the key to success is a fraud. The trouble is that folks on both extremes are bastardizing a very legitimate, time-tested hitting approach and are thus drawing lines in the sand about its application.

Just make sure when you see something out there about launch angle — or spin rate from the pitching side — you’re applying proper context and common sense. That goes double for any of you with kids who are being taught these things, since it can take a lot more time and effort to undo a bad habit than to develop a good one. Anyway, I hope I’ve been able to put things in perspective for those of you who actually managed to make it this far.