Launch Break: Why Kris Bryant’s Trademark Metric Has Gone Down in Resurgent Season

Kris Bryant is synonymous with launch angle. Between the combination of his rapid ascension from college ball to MLB that included just about every major award possible and a garrulous old man more than willing to extol the new-school application of old-school hitting techniques, it was inevitable. The correlation is so strong and the misunderstanding so deep in some cases that many outside observers can’t discern between process and results.

Baseball is a game defined by numbers and the results are what matter when you check the box score. And since we can’t all see the countless reps that go into creating a plate approach or a swing change, it’s natural that process would take a back seat when we evaluate a player’s performance in a game, series, or season. So while CI readers have had a picture window into Bryant’s adjustments for the last few years now, I’m not naive enough to think our reach can cover all of Cubs fandom.

Rather than go in yet again on rampant and unfortunate misconceptions when it comes to Bryant’s adjustments and performance, I want to look at what he’s doing in what some are calling #KBRevengeSZN. More importantly, I want to look at why and how he’s doing it because this isn’t a fluke.

I’m talking specifically about offensive numbers that rank in the top 10-20 in just about every category and that are on pace to better those of his 2016 MVP campaign. A lot can change, but he’s trending toward a career-best 9.5 fWAR at this point and he’s doing it all with an average launch angle of 13.5 degrees that is more than 7 degrees lower than in ’16 (20.8) and more than 5 degrees lower than his career average (18.9).

So that must mean he’s finally realized the error in his launchy ways, right? Actually, no.

The key, other than being healthy for the first time in way too long, is that Bryant has adopted changes meant to counter the way opposing pitchers are attacking him and the rest of his teammates.

“Throw them up and in and then down and away,” an opposing pitcher told ESPN’s Jesse Rogers. “That’s what you do with any hitter, but especially the Cubs.”

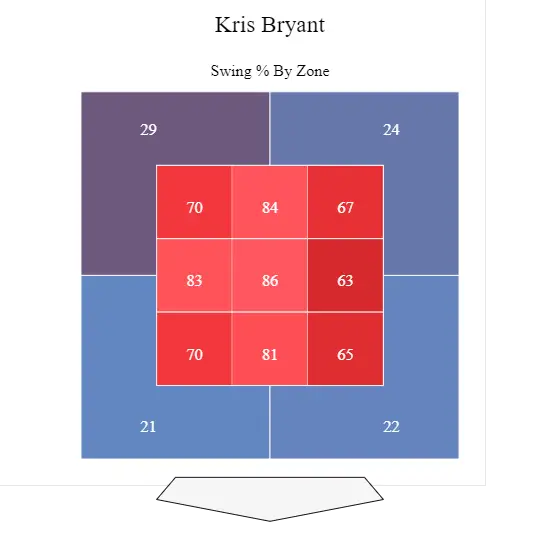

That is certainly the case for Bryant, who saw nearly 16% (93) of the 600 pitches he faced in 2020 up and in while another 30% (177) were down and away. Almost 36% (214) of the total pitches he saw were up in the zone, with just a few more of those on the inner half and even further in off the plate. After all, it makes perfect sense to attack a tall, long-armed slugger there before trying to get him to chase away.

The first half of that strategy worked well last season, though a lot of that came from Bryant being physically unable to catch up to those pitches. If you’ve ever tried to swing through wrist and/or finger injuries, you can understand why that might be.

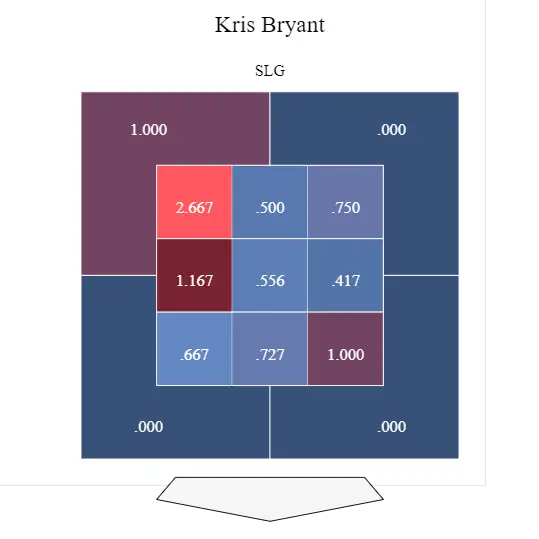

The results were obvious in his final line over the course of a season abbreviated by COVID-19 and a rash of injuries, but it can be illustrated just as easily in this slugging heat map. Other than middle-in and middle-middle/middle-low, KB simply wasn’t hitting anything with authority. His results were particularly bad against high stuff, even pitches in the zone.

Even though the sample isn’t quite large enough for everyone to consider it definitive, I’ve seen enough to know it’s a trend. With pitchers employing an identical location strategy (not pictured, so you’ll have to trust me), Bryant is displaying a better eye for the zone with fewer swings at balls. That shows in a 21.6% strikeout rate that’s lower than in any season other than 2017 and nearly 3% lower than league average so far in 2021.

Ah, but the real key here is what he’s doing when he does swing at those pitches, which is to say he’s crushing them. Just look at the marked improvement against pitches either in or up in the zone and check out how even a .667 slugging percentage is considered cold for Bryant right now. That 2.667 on pitches up-and-in is nothing short of absurd.

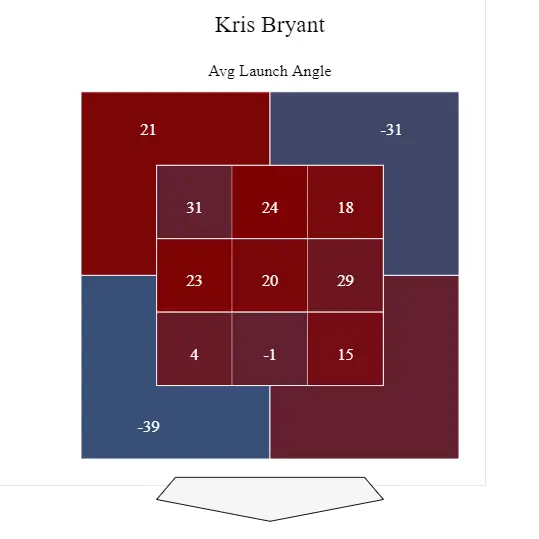

Now that we’ve established what he’s doing in general, let’s get to the whole point of this article as it pertains to Bryant’s reduced launch angle. He went into this season knowing he had to be better against pitches up in the zone, particularly high heat, so he tweaked his stance slightly and worked on keeping his hands higher to reduce the vertical angle of his swing plane.

As you can see from the charts below (2020 top, 2021 bottom), the result of these changes is that Bryant is generating less launch overall. Of note, most of that reduction is coming on pitches in the middle and lower portions of the zone, which makes sense when you figure that he’s aiming to better square up those high pitches.

If that sounds a little odd, consider that trying to hit the bottom half of a pitch up in the zone will result in being a little more square on a middle pitch and possibly catching the top half of a low pitch. Hence a 39.7% groundball rate that is the highest of his career and a 10.0% swinging-strike rate that is lower than ever. In general, you can see how there’s a little less uniformity in the way Bryant is launching the ball this season, with the numbers getting lower just as the pitches do the same.

There are, of course, exceptions based on the type of pitch he faces. I got a text from a friend prior to Monday’s game that “Launch angle works very good on curveballs,” a statement that quickly proved prophetic. After taking a fastball below the zone for strike one in his second at-bat, Bryant jumped on a Charlie Morton hook and hit it out with a 40 degree launch angle that’s far steeper than anything shown above.

Squaring that pitch up would have resulted in a grounder rather than a grand slam, so I’d say it worked out well.

The key to all of this is understanding that launch angle is merely the result of bat meeting ball and not necessarily a planned outcome. If a player sits back on a big curve and matches its steep plane, the result is naturally going to be a batted ball with a higher trajectory. Meeting a riding fastball more squarely or, ideally, on its bottom half is going to produce high line drives more often.

What we’re seeing from Bryant, then, is not the abandonment of his previous school of thought but merely the application of some adjustments to counter the ways pitchers are trying to beat him. That, and full health. The scary part for opponents is that Bryant can just as easily revert back to a slightly more vertical swing plane if the book on him says to stop trying to beat him high.

I said I wasn’t going to get into the misguided criticism of Bryant that has run rampant for the last few years, so I won’t. However, I’m happy to offer up a little salt or maybe even hot sauce for any of you who are eating crow this season.