Justin Steele’s Cut-Ride Fastball, Drew Smyly’s ‘Unicorn’ Churve Keying Success

Justin Steele is 3-0 with a 1.44 ERA while striking out nearly one batter per inning, and he’s doing it with just two pitches. Well, sort of. Standard classifications have him throwing his fastball at about a 62% clip and his slider nearly 36% of the time, but the latter can take more of a curveball shape and the former is a unique cut-ride offering that is really two different pitches.

“When I’m going in to righties, I’m thinking straight line through and keep bearing in on them rather than throwing it in and having it leak back over the plate,” Steele told Sahadev Sharma of The Athletic. “I’m kind of more on the side of the ball. Still throwing it with true spin, but it’s rotated a little bit so it stays in. When I’m going away to a righty, it looks like a ball the whole time and it just keeps riding and goes toward the plate.”

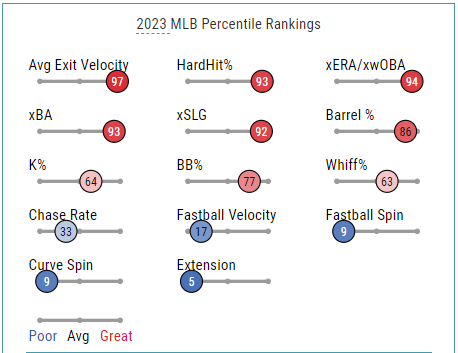

Being able to manipulate it as he does makes Steele’s fastball appear somewhat pedestrian from a data perspective, so you really have to see it in action to understand how it’s effective. His extension and velocity rank in the lower third of the league and almost all of his Statcast numbers are at or below the 81st percentile, but the batted-ball results are where he separates himself.

Hitters can’t really square him up, leading to upper-tier rankings in barrel rate, hard-hit percentage, and exit velocity. When combined with that slider, which is among the best in baseball, Steele is able to keep hitters guessing by making slight adjustments to produce unexpected movement.

“It’s funky, it’s relentless, and his fastball just kind of goes away,” Barnhart said. “It shows how good both of those pitches are. It’s hard to work your way through a lineup two or three times with two pitches, but he can do it.”

Drew Smyly has something similar with a knuckle curve that was operating with god-tier effectiveness on Friday against the Dodgers. The southpaw was perfect into the 8th inning and was actually undone by his own excellence, as David Peralta just got enough of a curve to nub it up the third base line and send Smyly and Yan Gomes careening into one another for one of the weakest hits you’ll ever see.

The hit Gomes made on his pitcher was harder than any of the contact Smyly allowed, you just have to be glad everyone could smile about it later.

Like Steele’s fastball, the numbers on Smyly’s stuff would tell you he shouldn’t be any good. Yet there he is striking out a batter an inning and limiting one of the most dangerous lineups in the NL to a single baserunner. In this case, the secret is that his curve kind of moves like a changeup by employing what is essentially the exact opposite strategy of Devin Williams‘ “airbender” monstrosity.

Where Williams hyper-pronates to create a ton of spin on the change, running totally contrary to traditional logic, Smyly generates some of the lowest spin numbers you’ll see on his curve. As Jordan Bastian broke down in great detail, the resultant shape has late floating break that allows Smyly to go front door on lefty batters or back door on righties to avoid barrels.

“It’s such a unicorn pitch,” said Cubs pitching coach Tommy Hottovy gushed.

“Hitters are so good at envisioning where the ball is going to end up,” Smyly said. “Because it fades, I think a lot of times, when hitters swing and miss, they get pissed off. They feel like they should’ve hit it.”

Just as you see with Steele, Smyly is effectively a two-pitch starter with the fastball and curve each accounting for nearly half of his offerings. He’ll throw a cutter now and then — actually more frequently than Steele throws his sinker, changeup, and curve combined — but not enough to really be considered a weapon. It’s all very counterintuitive, whether we’re talking about lefties in general or the current era of baseball.

Everyone seems to be adding new pitches or tweaking grips all the time to get more strikeouts and show up on Pitching Ninja’s feed, but there’s still plenty of value in simplicity. The key, of course, is to execute with intent. Steele and Smyly are both very good at what they do because they understand how to squeeze the most out of what both appear on the surface to be narrow repertoires.

This is the flip side of a Cubs pitching infrastructure that has been lauded for developing prospects and incorporating new pitches. Tommy Hottovy and his crew also know when to leave well enough alone and how to weigh the eye test against the metrics to discern what’s most important about a pitcher’s offerings. If the Cubs are going to keep winning this season, pitchability is going to play a huge role in their success.