Cubs Should Target Velocity This Winter, Plus Notes on Rules Changes

As infamous corporate raider Gordon Gekko might say, “Speed, for lack of a better term, is good.” That applies to both pitching velocity and game durations, the latter of which we’ll get to in just a bit here. Velo is obviously not the only factor in pitching success, but it has become the preferred currency in a sport that doesn’t accept credit. Well, other than the Ryan Express.

With that clumsy metaphor out of the way, we can get to one of the ways the Cubs can improve their pitching staff for 2024. According to Statcast, their 93.4 mph average fastball velocity ranked 26th in MLB and was seven-tenths off the overall average. That’s a jump from last year, when they finished dead last with 92.5 mph, but they’ve been no better than 21st since 2017 and were frequently in the bottom five in those seasons.

The last time the Cubs ranked in the top half of MLB’s velocity rankings was in 2016, when their 92.9 mph average was good for 11th. My memory has gotten fuzzy with age, so can anyone remind me what happened that season? Pretty sure it was good.

I’m not saying the Cubs need to top the leaderboards or anything, just that they need to find a better balance between power and finesse. Consider that they were tied for fourth with an overall 7.5% barrel rate allowed and came in second with an 88.3% exit velocity against. However, their 25.3% whiff rate was 21st and none of the teams below them on the list made the postseason.

All else being equal, velocity is the best way to increase a pitcher’s margin for error. As Oakland’s Brent Rooker recently noted on Twitter, it’s significantly harder to hit 97+ down the middle than to hit 92 on the corners. And to those who would say any good MLB hitters can time up elite velo when it’s over the plate, consider that none of the middle-middle fastballs of 102+ thrown in 2022 yielded hits.

It should also be noted that you don’t get to bring up Greg Maddux here because he’s not the best example of how the average big leaguer’s 92 mph sinker works.

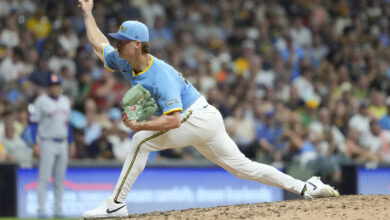

The Cubs were in the bottom third of the league when it came to the number of 99+ mph pitches thrown, pretty much all of which came from two pitchers. Outside of Julian Merryweather (98.2) and Daniel Palencia (98.6 between FB and SI), no other Cub averaged as much as 96 mph and only four were above 95. Nick Burdi (98) and Luke Little (96.6) sneak in there if we drop the innings minimum, so I guess there’s that.

Jed Hoyer addressed the media Tuesday for his annual end-of-season press conference, during which the team’s bullpen issues were discussed. He also spoke about the potential to keep Kyle Hendricks around and for Marcus Stroman to return for the third year of his deal. If both of those pitchers are indeed back, it’s hard to imagine the Cubs improving on the 92 mph average starters’ velocity that tied for last in MLB.

As such, they’re going to need to find more heat for a bullpen that Hoyer admitted didn’t have enough depth for the stretch run. Adding some hard throwers, whether it’s from the farm or in free agency, should be a priority for a team that will apparently continue to rely on getting outs via contact from the rotation. Hoyer has spoken for years about targeting strike-throwers who miss bats, yet it seems we see the same strategy of cobbling a relief corps out of retreads.

Don’t get me wrong, building fairly successful bullpens out of spare parts has been one of the bright spots for the Cubs even when they’ve had crappy overall results. It’s just that the real goal of those units was to leverage improved performance from guys on short, cheap deals for trade returns at the deadline. A team that truly intends to compete can’t sail into October in a boat held together by Flex Tape and prayers.

Hoyer needs to go out and load up on dudes who throw gas, plus he needs another two or three position players who hit tanks.

Game durations lowest in 20 years

I always found it odd when people waxed romantic about being forced to watch baseball games that lasted over three hours. Do they have nothing better to do than watch a reliever patrol the mound for a minute between pitches or observe the nuances of a batter adjusting his gloves 15 times after a take? Anyone who complained about a pitch clock artificially shortening game times had it backwards.

The length of an average MLB game has actually increased significantly over time, to the point where it was at least 180 minutes in eight of the nine previous seasons. In 2023, however, the average time was reduced to 2:39 as a result of the pitch clock. That’s 24 minutes faster than last year and 31 faster than in 2021, so kudos to MLB for getting something right.

More steals

With the exception of the Braves stopping a game with playoff implications in extra innings to celebrate a round number, I am a big fan of the rules to aid steals. Bigger bases and disengagement limits spurred runners to swipe bags at a rate we haven’t seen in nearly 40 years. The 3,503 total steals represented a 41% jump over last season (2,486) and marked MLB’s highest total since 1987 (3,585).

What I find really interesting is that the distribution is more equitable now than it was back then, when Vince Coleman stole 109 bases and 33 players had at least 25 swipes. This season saw Ronald Acuña Jr. lead the way with 73 while just 18 players had 25 or more. In total, 437 players stole at least one bag this season, as compared to 366 back in ’87.

This addresses a bigger issue than just the length of games, which is the actual pace of play. Those things get confused way too often even though they’re distinctly different concepts. A long game can feel like it’s flying by if there’s a lot of action, while a shorter contest can drag out in the viewers’ perception if it’s uneventful. More action on the bases increases the excitement level and that’s a good thing.

Now we just need to get the automated ball-strike system in place to correct those 21,000 missed calls by umpires in 2023.

How do you feel about the new rules and are there any you’d like to see eliminated? Better yet, what other guidelines should be implemented in the future?