Enough Patience Already, Time to End Jason Heyward Leadoff Experiment

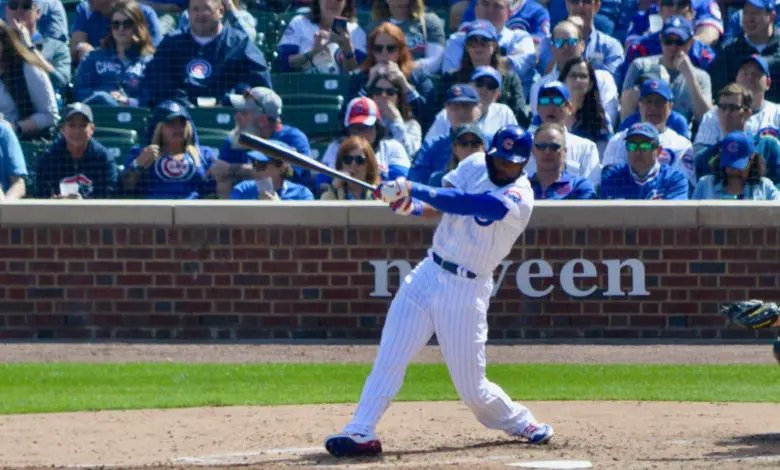

By all accounts, Jason Heyward is a good dude. And up until the last month or so, it appeared as though his play on the field was going to measure up to the expectations, realistic or otherwise, that fans had for him after signing that big free-agent deal ahead of the 2017 season. Then leadoff happened.

Batting primarily in the bottom half of the order through July 30, Heyward amassed a .278/.355/.458 slash with a 109 wRC+ that included 15 homers and 44 RBI. That dinger tally was his highest since he hit 27 for the Braves in 2012, and he was on pace for his best season in Chicago. Though he is still on said pace, that production has ground to a halt as the Cubs have stubbornly stuck with him at the top spot in the order.

Some that, maybe all of it, is per Heyward’s request. He was reluctant to take over the role in the first place and asked for some assurances before accepting it at the the end of July.

“It’s about me wanting to make the most of my time playing baseball,” Heyward told MLB.com in early August. “Whatever works best, I’m going to try and do that. And right now, that’s what they feel is best, so let’s go. I just asked Joe to be patient with me. Just give me a shot and here we go.”

Maddon has definitely been patient with Heyward, giving him nearly a month to get comfortable at the top of the order, but there’s just no way the Cubs can still feel that is best for either Heyward or the team. They gave it a shot and we’re seeing a little more clearly each day that it’s really not working out.

For a little while there at the start, though, it looked like Heyward was indeed going provide a shot in the arm for broken offense that still isn’t fixed. Through his first 26 plate appearances since taking over at leadoff, Heyward got out to a 130 wRC+ with a pair of homers, a double, and a triple. There was maybe a little concern because his strikeouts were up and his walks were down, resulting in a stifled OBP, but small sample and all that.

The walks and strikeouts have balanced out in the time since, both sitting better than his career averages, but his slash has fallen to .159/.303/.254 with a 57 wRC+ that’s almost half of what he’d been putting up earlier in the season. Heyward’s hard contact is down five percentage points, his groundball rate is up 16 points, and his pull rate (49%) is higher than during any previous campaign.

With the understanding that one month does not a season make, it’s still enough time to see that something just isn’t working. Of course, nothing else has worked very well for the Cubs when it comes to the leadoff spot either. It’s almost as though exposure to it has deleterious effects on the player in question, eroding his skill gradually until he’s just a husk.

Look at Kyle Schwarber, who tinkered with his approach in more than one failed attempt to figure things out before finally settling into something sustainable in August, well after being removed from the top spot. As a whole, the Cubs are hitting .207/.284/.384 with a 72 wRC+ from the leadoff spot. The MLB average, for what it’s worth, is .252/.331/.450 with a 100 wRC+.

To put it as simply as possible, the production the Cubs have gotten at leadoff is 28% worse than what they should be getting. Okay, cool, but what’s the answer? After all, it’s a total bush league move to point out a problem and not offer a solution, the realization of which is why Cubs Insider is even a thing. But I digress.

Remember that stuff about the leadoff spot having some sort of negative force that drains the energy from the players in its vicinity? I really believe there’s something to that. For the Cubs, it’s as though leading off has taken on the air of a haunted house since Dexter Fowler’s departure. Like an urban legend that grows over time, each new leadoff hitter who failed to fill those Air Jordan cleats added a new layer to the mythology.

In a game that relies so heavily on the mental acuity of its practitioners, the slightest disruption or trepidation can detract significantly from performance. So even if a new player summons up the intestinal fortitude to go knock on Old Man Fowler’s door, he ends up running away soon enough. A little too dramatic? Perhaps, though I have no regrets for the analogy.

As such, I believe the best option is to operate without a set leadoff hitter at all. Rotating that spot between a few different hitters keeps any of them from falling into bad habits formed by employing different swing thoughts for more than a game or two at a time. It also allows Joe Maddon to exploit different matchups, something he can’t do with Heyward — or any non-switch-hitter — at the top.

For instance, Heyward has been far worse against left-handed pitchers, slashing .071/.235/..071 with a -1 wRC+ against them as a leadoff man. Under no circumstances should you be looking to spark your offence with a guy who is 101% worse than an average hitter. Makes zero sense.

Instead, maybe Maddon could try Kris Bryant and his .461 OBP with a 194 wRC+ against southpaws. Or Nicholas Castellanos and his .433 OBP and 188 wRC+, which might make even more sense because he’s essentially served as a leadoff hitter since he’s batted behind Heyward during his time as a Cub. Willson Contreras is another option once he returns, as is Ben Zobrist.

Then you go with Anthony Rizzo every once in a while, since he’s the Greatest Leadoff Hitter of All Time. Moving another lefty bat up there from time to time against righties isn’t a bad idea either.

That might sound a little crazy, but it’s not as though going with a static option has worked out too well for anyone thus far. By moving a few guys in and out of that spot in something of a rotation, almost like starting pitchers, Maddon could establish a routine while still avoiding side effects that can develop over prolonged exposure to the leadoff stigma. It also puts Heyward back where he’s more comfortable, thereby allowing him to break out again.

Or, you know, he can just keep running Heyward out there in the hope that something clicks and he gets back to those earlier numbers. As Jed Hoyer said, though, “hope is not a plan.”